What's the True Risk of Dying from Eating Raw Oysters?

Spoiler alert: your odds of drowning in a bathtub are greater.

“Eating raw oysters can KILL you!”

If you've read any mainstream news articles about oysters and Vibrio bacteria, you’ve probably seen sensationalized warnings like this. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) issues strong public health alerts about the “dangers” of eating raw oysters, warning about life-threatening infections and urging people to avoid them altogether. And yet, we know that oysters are among the most nutritious foods on the planet, packed with essential vitamins and minerals that support human health.

While I deeply respect the CDC’s mission to protect public health, I can’t help but feel they have missed the mark when it comes to communicating the real risks of consuming raw oysters.

Worse, journalists and content creators frequently misinterpret CDC health advisories, conflating vague Vibrio statements in ways that exaggerate the dangers of oysters far beyond reality. Unfortunately in many cases, they are incentivized to create a stir.

I mean, it really can’t get anymore clickbaity than this:

So, what exactly is your likelihood of dying from this so-called “flesh-eating bacteria” through the consumption of raw oysters? To answer that, we first have to understand a few things about Vibrio and how it’s monitored in the U.S.

Understanding Vibrio

Vibrio is a group of bacteria naturally found in coastal waters. They are pretty ubiquitous and their presence has nothing to do with pollution. They only grow in warm waters and become undetectable when temperatures dip below 50F.1

There are about a dozen species that can cause a human illness called vibriosis. You probably know of Vibrio cholerae, the bacterium responsible for cholera, but the most common species causing human illness in the United States are:

Vibrio alginolyticus

Vibrio parahaemolyticus

Vibrio vulnificus — a.k.a. the “flesh-eating” bacteria

I won’t go into the causes and symptoms of each in this post, but I do want you to know that the severity of infection or complications from each kind can vary greatly. Not all Vibrios are created equally.

About 20% of Vibrio vulnificus cases result in death, but nearly all occur in individuals with serious pre-existing health conditions or compromised immune systems.

By contrast, only ~1% of Vibrio parahaemolyticus cases result in death. Most people just have a few days of diarrhea.

Vibrio alginolyticus is likely to cause a skin wound infection or an earache.

So while Vibrio vulnificus can truly be dangerous, getting serious complications from it is extremely rare amongst health adults.

How the U.S. monitors and reports Vibrio

The U.S. monitors Vibrio infections through two key surveillance systems: COVIS (Cholera and Other Vibrio Illness Surveillance) within the NNDSS (National Notifiable Diseases Surveillance System) and FoodNet (Foodborne Diseases Active Surveillance Network). Together, these systems help identify outbreaks2, track seasonal patterns, and guide seafood safety policies.

COVIS, managed by the CDC, FDA, and state health departments, specifically tracks illnesses caused by Vibrio species, including those linked to raw oysters and marine wound exposure. Their reports break down vibriosis cases by species and by foodborne and non-foodborne transmission routes.

Meanwhile, FoodNet, a broader surveillance program operated by the CDC in collaboration with the USDA, FDA, and 10 state health departments, collects data on multiple foodborne pathogens, including Vibrio, to assess national trends in foodborne illness.

There are two primary methods for diagnosing Vibrio:

The traditional culture-based method, which isolates and identifies bacteria.

The newer culture-independent diagnostic tests (CIDTs), which detect bacterial DNA directly from patient samples without the need for culture. CIDTs are growing in popularity because they are faster and cheaper to administer. However, they lack key details obtained through traditional culturing, such as species identification and antibiotic resistance.

Knowing this detail comes into play later on…

Looking at the Vibrio data

According to the CDC’s webpage on vibriosis, the agency estimates that 80,000 Vibrio infections occur each year in the U.S. and about 52,000 of those cases are linked to eating contaminated food.

Sounds like a lot, right? But here’s the thing:

The 80,000 figure is a statistical extrapolation, not confirmed diagnosed cases. There’s no further information on the page about the projected breakdown of species or the calculation method.

In 2023, FoodNet reported only 501 laboratory-confirmed Vibrio infections3 across its surveillance area.

In 2019, COVIS reported 2,719 Vibrio infections nationwide4, the most recent year with available data.

CDC’s FoodNet Fast graph of Vibrio infection (all species) incidence per 100,000 population from 2012 to 2022.

There are likely many mild Vibrio infections that go unreported or undiagnosed. Since 2015, the increased use of CIDTs has contributed to a rise in reported Vibrio cases. However, this doesn’t necessarily indicate an actual surge in infections—rather, it probably reflects improved detection. Distinguishing between a true increase in cases and better diagnostic reporting remains challenging, though it’s likely a combination of both.

As mentioned earlier, the trade-off with CIDTs is that, unlike traditional culture-based methods, they do not identify the specific Vibrio species responsible for infection. This is a critical limitation because the severity of illness varies significantly between species. Without species-level data, it becomes harder to assess public health risks accurately and could lead to misleading generalizations about Vibrio-related illnesses. Sound familiar?

Among Vibrio vulnificus, the deadliest strain (and the one that the media tends to associate raw oyster consumption with), roughly 150-200 cases are reported annually. But here’s the kicker: most are NOT caused by eating contaminated food! The majority of Vibrio vulnificus infections come from non-foodborne transmission routes, such as exposing wounds to seawater.

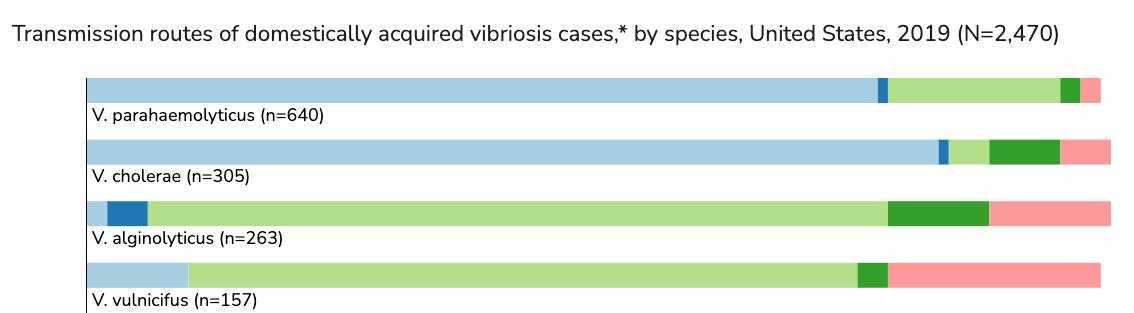

Take a look at this transmission route breakdown from the most recent 2019 COVIS report:

Eating a bad oyster is an extremely unlikely dumb way to die

Let me be clear: getting vibriosis from Vibrio vulnificus is far more likely from an open wound than from eating raw oysters. Yet, the CDC tends to put the two sources on equal footing in their public messaging.

But just to further emphasize the difference between the data and public perception, let’s focus specifically on the worst case scenario—fatalities caused by Vibrio. The most recent FoodNet report (2023) identified 5 deaths from Vibrio in its surveillance areas, which represents about 16% of the U.S. population. When extrapolated nationwide—assuming Vibrio cases and deaths are proportionally distributed—the estimated number of Vibrio-related deaths is around 31 per year. To put that into perspective:

Odds of dying from Vibrio (from any transmission source): ~1 in 10.6 million per year based on extrapolation of confirmed reported cases. Then, just to be ultra conservative, let’s multiply those odds by 100. So our new risk assessment would be 1 in 106,000 per year.

Higher risks5 you rarely hear about:

Dying from a dog attack: ~1 in 44,500

Dying in a cataclysmic storm: ~1 in 39,000

Drowning in a bathtub: ~1 in 6,000

Dying from choking on food: ~1 in 2,500

Does that put things into perspective? If not, let’s then compare Vibrio-related deaths to other foodborne pathogens:

Salmonella: ~450 deaths per year6

Listeria: ~260 deaths per year7

E. coli (STEC O157 and others): ~100 deaths per year

This means that you’re far more likely to die from Listeria in cheese, Salmonella in poultry, E.coli from spinach, or from choking on your dinner tonight than from Vibrio in oysters.

The overlooked Vibrio parahaemolyticus

While Vibrio vulnificus gets the most media attention due to its severe but rare cases, the real Vibrio species of concern in raw oysters is Vibrio parahaemolyticus. Unlike V. vulnificus, which is mostly contracted through open wounds, V. parahaemolyticus is the leading cause of foodborne vibriosis, making it far more relevant to the oyster discussion.

Bob Rheault, Executive Director of the East Coast Shellfish Growers Association and widely known as the ‘Vibrio Evangelist,’8 addressed oyster shucker and restaurant owner concerns during a discussion hosted by the Oyster Master Guild. He noted that V. parahaemolyticus cases are far more common than V. vulnificus, but rarely severe:

“V.p. does sicken a lot more people, but it’s nowhere near as severe. It will typically cause a self-limiting case of gastroenteritis—an unpleasant couple of days, but that’s about it.”

Live shellfish is one of the most highly regulated food products out there and the oyster industry overall does a fantastic job with complying to the FDA’s rigorous requirements. Bob noted in his talk:

“The vast majority of Vibrio management and mitigation happens at the farm level. Growers are quite conscientious... On my farm, we would get our product out of the water and into the walk-in cooler in about a half an hour… I’ve been running around teaching my growers how important it is to get their product cold... Most states now mandate two hours to refrigeration during the summer months.”

Proper handling and storage of oysters—keeping them at or below 45°F9—can significantly reduce the proliferation of Vibrio and risk of illness.

In his concluding remarks, Bob emphasized that individuals with compromised immune systems or those taking immunosuppressant medications should avoid raw oysters and opt for cooked ones instead. For everyone else, the key is simple: use common sense.

Final takeaways: the greater risk of not eating oysters

While much of the public health conversation fixates on the small risks associated with eating oysters, I believe that the far greater health consequences come from not eating enough oysters and other seafood. Oysters provide essential nutrients like omega-3 fatty acids, zinc, vitamin B12, selenium, and iron, all of which are critical for brain function10, heart health, immune support, and overall longevity.

Avoiding oysters due to an exaggerated fear of Vibrio means missing out on one of the most nutrient-dense, sustainable foods available. The real conversation should be about balance: understanding actual risks versus perceived risks and making informed choices accordingly.

I hope this analysis puts Vibrio-related illness into perspective. Everything in life comes with risks and rewards. For me, the benefits of eating raw oysters far outweigh the risks—and encouraging others to enjoy them responsibly is a far greater public health service than unnecessary fear mongering.

Yoon JH, Lee SY. Characteristics of viable-but-nonculturable Vibrio parahaemolyticus induced by nutrient-deficiency at cold temperature. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2020;60(8):1302-1320. doi: 10.1080/10408398.2019.1570076. Epub 2019 Jan 31. PMID: 30701982.

Vibriosis is a nationally notifiable disease in the U.S., meaning healthcare providers and labs are required to report cases to state and local health departments, though reporting requirements vary by state.

CDC FoodNet Surveillance Report (2023 Data): Reported Incidence of Infections Caused by Pathogens Transmitted Commonly Through Food: Foodborne Diseases Active Surveillance Network, 1996–2023 (July 4, 2024)

CDC Cholera and Other Vibrio Illness Surveillance (COVIS): Annual Summary, 2019 (Latest report available as of this post)

Preventable Deaths: NSC Injury Facts: Odds of Dying

I highly recommend checking out Bob’s blog post, “The Truth About Flesh-Eating Bacteria.”

Scientists are currently studying how climate change may influence Vibrio growth, as warming waters could expand its range. However, it remains unclear how much this directly impacts illness rates per meal, as mentioned early, better diagnostic testing has also increased case detection.

One of the most compelling scientific reviews that I’ve seen: Relationships between seafood consumption during pregnancy and childhood and neurocognitive development: Two systematic reviews